Consequences of Using an Off-Calendar Plan Year

Just like a company, a retirement plan is required to operate on a set 12-month period. This is often referred to as the tax year or fiscal year for a business and a plan year for a retirement plan. Also similar to many companies, many retirement plans elect to use the calendar year as that 12-month period. But just because most businesses/plans operate that way does not mean that all of them must.

While some business owners and accountants prefer to have the retirement plan operate on the same year as the business, there is no legal requirement that the two align. And, as we will describe in this article, there are several compliance reasons why it might make sense to have the plan year line up with the calendar year even if the company’s fiscal year is different.

Data Collection

Most payroll systems can easily produce annual employee census reports that follow the calendar year, as this is generally the same information that is required to prepare the Forms W-2 each January. However, some systems are limited in the reporting they can produce for periods that cross calendar years. For an off-calendar plan year, that could mean generating and combining two reports – one for the portion of each year that comprises the plan year. While not necessarily difficult, the extra steps can be time-consuming. Not to mention, each time the data is manipulated is one more opportunity for errors to occur.

Plan Eligibility and Entry

It is fairly common for a company to require a new hire to complete a year of service before being eligible to join the retirement plan. While it might sound simple, a year of service is often defined as 1,000 hours of service during the plan year. If the plan operates on an off-calendar year, then hours must also be measured on that same off-calendar year in order to properly determine when a new hire becomes eligible.

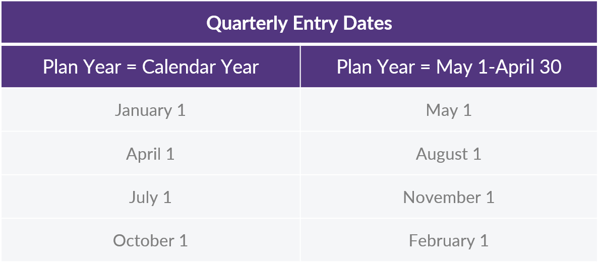

Similarly, plan entry dates (the dates someone actually joins the plan once they satisfy the eligibility requirements) are often defined as the first of the quarter or each semi-annual date. For calendar year plans, these dates are easy to manage; however, for off-calendar plan years, it is important to identify whether the first day of the quarter is really defined as the first day of every fourth month of the plan year.

Contribution and Benefit Limits

The interacting contribution and benefit limits can be confusing enough on their own, but trying to apply them when using an off-calendar plan year can be even more of a conundrum. Here are several reasons why.

401(k) Deferral Limit

The IRS limits the amount a person can defer into a 401(k) plan each year, including catch-up contributions. Because that limit has implications with respect to each individual’s income taxes, the annual dollar limit is always applied on a calendar year basis regardless of the year on which the plan operates. Consider this example:

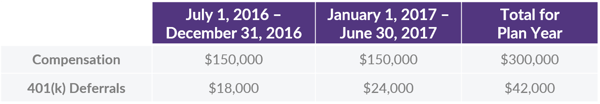

Audrey is a participant in the Great Northern 401(k) plan that operates on a plan year that runs from July 1st to June 30th. The current 401(k) deferral limit is $18,000 per year, and the catch-up contribution limit for those who are age 50 and older is an additional $6,000 per year. Audrey turns 50 in January of 2017.

Audrey’s deferrals for calendar year 2016 are limited to $18,000, but she is able to defer $24,000 for calendar year 2017 ($18,000 in “regular” deferrals + $6,000 in catch-up contributions). That means it is possible for her to defer a total of $42,000 for the plan year without exceeding the limit for either calendar year.

It is critical to ensure that the payroll system is set up to properly monitor these limits for each calendar year, even though the plan operates on an off-calendar year.

Annual Additions Limit

This is the cap on the total contributions any single participant can receive in a single plan year from all sources, including both employee deferrals and company contributions. For 2016, the cap was lesser of $53,000 or 100% of the participant’s total compensation. The dollar cap is $54,000 for 2017 and is indexed for inflation in $1,000 increments for each year, thereafter. Catch-up deferrals by those over age 50 do not count toward the annual additions limit.

Easy enough, but how is the limit applied in an off-calendar situation? The limit is based on the calendar year in which the plan year ends.

Let’s return to our example of Audrey at the Great Northern 401(k) Plan. The maximum amount Audrey can receive for the plan year that runs from July 1, 2016, through June 30, 2017, is $54,000 because that is the annual additions limit that applies for 2017.

That might seem fairly straightforward; however, considering the fact that Audrey could potentially defer $42,000 for that plan year, any contributions the company might make on her behalf could be significantly curtailed based on the annual additions limit.

Annual Compensation Limit

The IRS also places a limit on the maximum compensation that can be considered for any single participant in a given year. The limit for 2016 is $265,000, and the limit for 2017 is $270,000. For future years, it is indexed for inflation in $5,000 increments.

Unlike the annual additions limit, the annual compensation limit for an off-calendar plan year is based on the limit that applies for the calendar year in which the plan year begins.

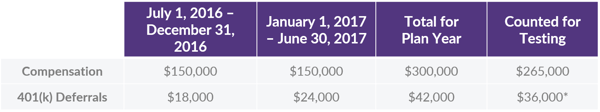

Back to our friend Audrey. Assume her compensation remains unchanged at $300,000 for both 2016 and 2017. The maximum pay that can be considered for her for the 2016/17 plan year is $265,000, because that is the limit that applies for the 2016 calendar year (the one in which the plan year begins).

Other Limits

Thankfully, there is some consistency. Most of the other limits, including those for identifying highly compensated and key employees follow the same logic as the annual compensation limit, i.e. the limit is based on the calendar year in which the plan year begins.

Calculating Company Contributions

The use of an off-calendar plan year can also have unintended consequences on how company contributions are calculated, particularly with respect to higher paid employees, as Audrey will show us. Here is a summary of her compensation and 401(k) deferrals for the plan year.

Matching Contributions

Let’s assume that Great Northern uses the relatively common match formula of 50% of the first 6% deferred by each participant, which yields a maximum match of 3% of pay. Recall that the maximum compensation we can use for Audrey for the plan year is $265,000. That means she has deferred a total of 15.85% of her eligible pay.

Audrey’s matching contribution for the plan year is $7,950 (or 3% of $265,000). Since she “shifted” her full deferral limit for both 2016 and 2017 to fit in a single plan year, that $7,950 would be the maximum match she could receive for that two-year period.

Assume, instead, that the plan operated on a calendar year. Because the annual deferral limit would then be in line with the plan year, Audrey’s matching contribution over the two-year period would be $16,050 (3% of $265,000 for 2016 + 3% of $270,000 for 2017).

Profit Sharing Contributions

By shifting all of her deferrals into a single plan year, Audrey is also limited in how much of a profit sharing contribution she can receive. The annual additions limit for the plan year is $54,000 (not counting catch-up contributions), so the maximum profit sharing contribution Audrey could receive is $18,000 or 6.79% of pay. If Great Northern makes both a match and a profit sharing contribution, Audrey’s maximum profit sharing is only $10,050 or 3.79% of pay.

Nondiscrimination Testing

The interplay of the limits noted above can also have a significant impact on the annually required ADP test, which is the nondiscrimination test that applies to 401(k) deferrals. A detailed description of the test is available here, but the gist is that it compares the average deferral percentages of the HCEs to those of the NCHEs. If the spread between the two groups is more than 2 percentage points, the HCEs must get a refund or the company must contribute more on behalf of the NHCEs. Let’s see how that plays out for Audrey.

*Excludes catch-up deferrals

While it is theoretically possible that non-HCEs could help the test by also deferring large amounts, they are less likely to be able to afford to do so. Based on these contribution and compensation levels, Audrey’s deferral rate for the plan year is 13.58%. That is certainly going to drive up the average of the HCE group and make it more difficult to pass the ADP test. If Audrey is the only HCE in the Great Northern 401(k) Plan, the non-HCEs would have to defer, on average, well more than 10% to pass the test.

Reporting

Many reports and participant disclosures are prepared on either a calendar year or calendar quarter basis. These range from the quarterly participant statements prepared by many recordkeepers to many financial publications and websites that report investment performance. As a result, operating on a non-calendar plan year can be confusing to participants and it can make comparing performance more difficult for both participants and the plan fiduciaries who are charged with monitoring the fund menu.

Conclusion

While there is nothing inherently wrong with using an off-calendar plan year, you can see that doing so can significantly add to the complexity of maintaining the plan. Even if you are working with an experienced third party administrator like DWC, it is critical to have solid internal controls to ensure there are no missteps during the year even before it’s time for your annual compliance review.

If you have an off-calendar plan year, we would be glad to work with you to review your processes to ensure they cover all the bases. And, if you’d rather change your plan to operate on a calendar year, we can help you with that also.

For more information on plan sponsor deadlines and requirements, visit our Knowledge Center.