Delinquent Deposits of Employee Deferrals? There's a Fix for That!

While it might not seem like that big of a deal if 401(k) deposits are made a couple days or weeks late, the Department of Labor (DOL) considers those payroll withholdings to be plan money on the deposit deadlines regardless of where the money is physically located. To the extent those monies are still in the plan sponsor’s control, the delayed deposit is treated as a prohibited loan of plan assets to the plan sponsor, which is a very big deal (not in a good way). If that wasn’t motivation enough to fix the delinquency, the fact that late deposits must be reported on the Form 5500 each year until fully corrected (which is like waving a red flag in front of a bull, only the bull here is the DOL) certainly should be motivation to fix it. Pronto!

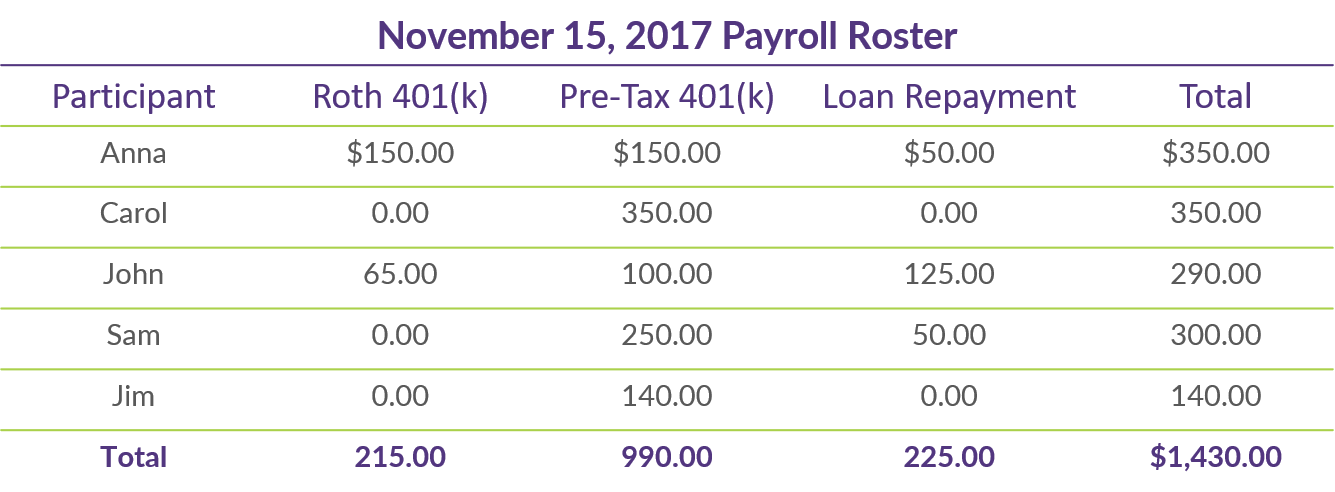

Almost On Time, Inc. sponsors the AOT 401(k) Plan. It has 45 participants and the following pertinent details:

- Operates on a calendar year,

- Files as a small plan, i.e. fewer than 100 participants,

- Has semi-monthly payroll (1st and 15th of each month),

- Allows for both pre-tax and Roth deferrals, and

- Permits participant loans.

Within a day or two after each pay date, the Human Resources director makes the following deposit to the recordkeeping platform:

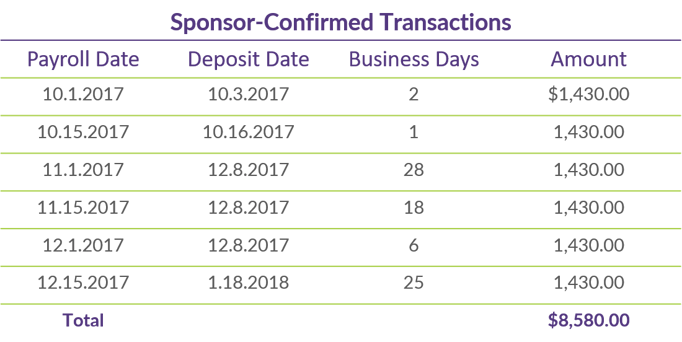

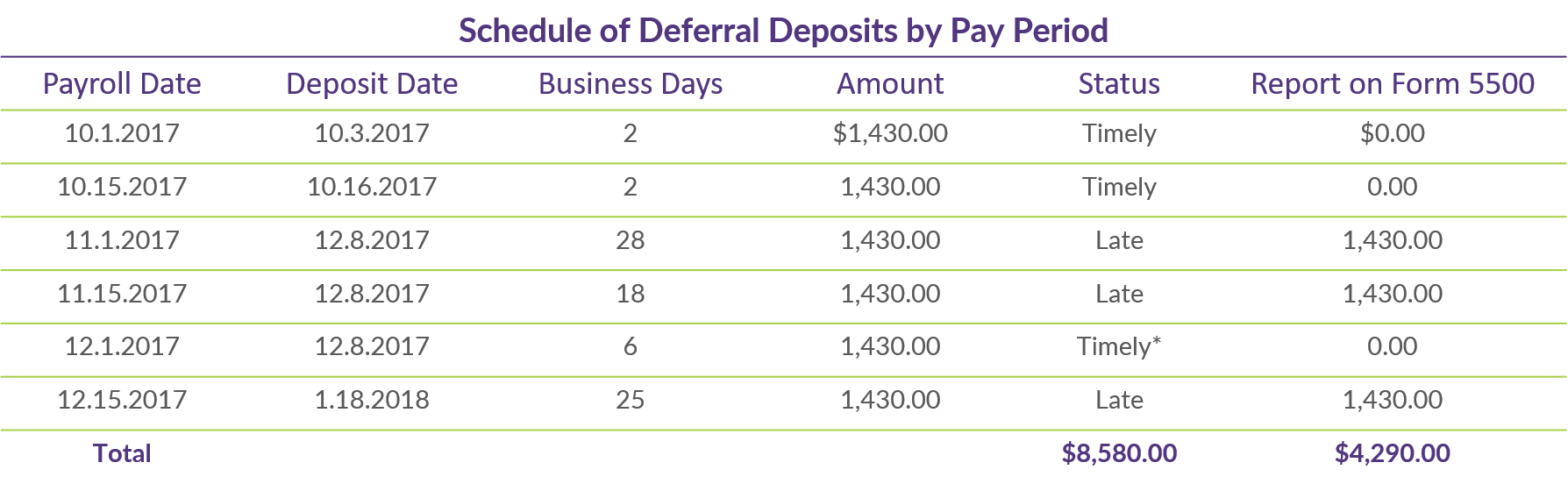

In early 2018 while completing the annual compliance review for 2017, the TPA discovers several deposits outside of the usual timing, all of which occurred while the HR director was out on a leave of absence. On full review of the leave period, AOT confirms the following deposit dates:

DOL regulations specify an outside deadline for depositing employee contributions to a plan; however, the earlier part of that same regulation makes it clear that plan sponsors must make deposits as soon as the amounts in question can reasonably be segregated from the company’s general assets. The DOL created a safe harbor standard for plans with fewer than 100 participants, which states that regardless of how quickly the sponsor is able to reasonably make the deposit, the DOL will treat it as timely if made within seven business days following the payroll date.

Since AOT deposited the contributions from the November 1st, November 15th, and December 15th payrolls more than 7 business days after the pay dates; DOL considers these deposits to be late – each a prohibited transaction in need of correction.

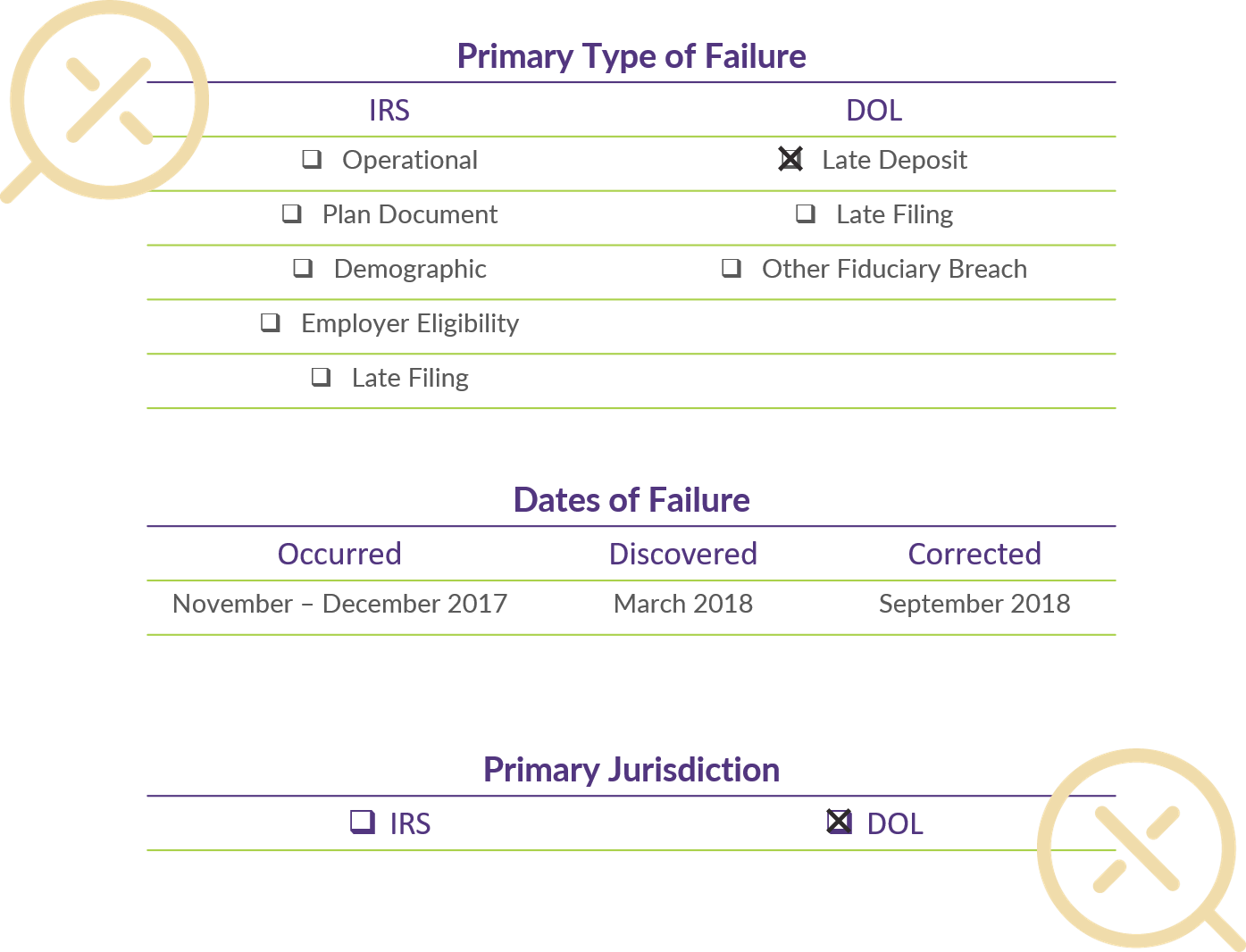

Error Details

Note: Late deposit of participant deferrals and loan payments must be reported on the annual Form 5500/5500-SF filing each year until fully corrected. Sponsors reporting delinquent deposits are a red flag for the Department of Labor and, oftentimes, these filings result in follow-up correspondence from the Department when corrections through VFCP are not completed.

As with all plan corrections, the basic premise is to put the plan, and its participants, back in to the position they would have been in had the error not occurred. In the case of late, the plan sponsor must make participants whole for the lost earnings opportunities that occurred. In addition, the plan sponsor files a Form 5330 with the IRS to disclose the details of the late deposits and pays an excise tax as penalty for the prohibited transaction(s).

Summary

In general, the correction of delinquent deferrals and loan repayments consist of the following steps.

- Identify the contributions deposited beyond the regulatory deadline.

- Calculate the lost earnings due the participants.

- Deposit and allocate lost earnings to the affected participants for each late deposit.

- File a Form 5330 with the IRS for each affected year to pay the excise taxes.

- Report late deposits on the Forms 5500 for each year until full correction is made.

- Request DOL approval of the correction via the Voluntary Fiduciary Correction Program (VFCP).

Application

Identify Late Deposits

The first step is to identify all contributions deposited after the deadline. In addition, if any of these deposits are still pending, the plan sponsor should get them into the plan as soon as possible before proceeding with the correction process.

*Note that under the general standard, the DOL would likely also consider this deposit to be late. The reason is because the plan sponsor has demonstrated it is capable of making the deposits within just a day or two following payroll per the October 1st and 15th pay dates. However, because this is AOT is a small plan filer, it qualifies for the seven-business-day safe harbor, making the deposit from the December 1st pay date timely.

Restitution for Lost Earnings

The next step is for the plan sponsor deposits lost earnings to the affected participant accounts to compensate them for lost investment gains for the delay between when the deposit should have occurred and when they actually occurred.

The lost earnings for each late deposit are based on an “underpayment” rate published by the IRS each calendar quarter. The DOL provides an online calculator to assist with these calculations. It requires four inputs for each late deposit:

- Principal: the total amount of the late deposit, i.e. the sum of the deferrals and loan payments.

- Loss Date: the date the deposit should have been made.

- Recovery Date: the date the deposit was actually made.

- Final Payment Date: the date the lost earnings will be deposited. Note that this date cannot be any later than 30 days following the date the lost earnings amount is calculated.

The total ($10.22 in this case) is then allocated among all affected participants. The calculation of lost earnings and the allocation among participants must be performed separately for each late deposit.

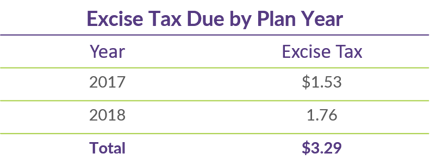

Form 5330 - Excise Taxes

The IRS assesses an excise tax on all prohibited transactions, and late deposits are no exception. The excise tax is equal to 15% of the “amount involved” (the amount of the lost earnings in this case). While that sounds straight-forward, the calculation can be rather complex. One of the main reasons is that any late deposits not fully corrected by the end of a year are considered re-occurring each subsequent January 1st. In addition, any lost earnings not deposited by the end of a year are considered to be new prohibited transactions as of each subsequent January 1st. This creates a sort of cascading effect, which can exponentially multiple the number of prohibited transactions requiring lost earnings.

We won’t subject you to all of the detailed calculations, but after all is said and done, the total excise tax due in this situation is $3.29.

If you are shaking your head that we have spent this much time and effort to arrive at a total of $10.22 in lost earnings and a total excise tax of $3.29, you are not alone. Many of the prohibited transaction rules were written before 401(k) plans existed, so applying them in this context can lead to some unexpected results. Nevertheless, those are the requirements that plans must follow to fully correct late deposits.

Note: For Form 5330 purposes, the prohibited transactions are not fully corrected until after both the delinquent amounts and related earnings have been deposited to the plan.

Form 5500

The Form 5500 includes a question about whether the plan experienced any late deposits. This is another seemingly straight-forward part of the correction that has a bit of wrinkle. When completing that question, the plan sponsor must list not only any late deposits that occurred during the year in question but also any previous late deposits that were not fully corrected before the year started. In the case of Almost On Time, Inc., they must report the late deposits on the 2017 Form 5500 (the year the late deposits occurred) and again on the 2018 Form 5500 since the corrections were not completed until that year).

Voluntary Fiduciary Correction Program

DOL’s official position is that they do not recognize self-correction of late deposits. In previous years, a footnote on the Form 5500 to confirm correction was enough to make the DOL look the other way. More recently, however, DOL has taken an approach more in line with their stated position and has contacted sponsors reporting late deposits on their Forms 5500 to “invite” them to submit a VFCP application. Suffice it to say, that is not an invitation to be declined unless one enjoys the prospect of a formal DOL audit/investigation.

Ultimately, it is a judgment call for each plan sponsor to decide whether they wish to go the VFCP route or play the audit lottery. Submitting through VFCP is the only way to formally correct and close the book on delinquent deposit and to ensure a clean bill of health in the eyes of the DOL.

Bad things happen to good plans. If you've experienced a failure like this, or are combating other issues, DWC is here to help with Plan Correction Services to address any "oops" moments in your plan.

RELATED RESOURCES