Distributions from a Retirement Plan

Ask just about any service provider who works with retirement plans what their most frequently asked questions are, and they will likely tell you that they all relate to how and when participants can get their money out of the plan. After all, it’s easy, right? Put money in the plan; take money out of the plan. Some providers treat distributions like speeding down the highway, thinking it’s not that big of a deal as long as you don’t drive too far over the speed limit. However, failure to follow the rules of the distribution road can be far more expensive than a speeding ticket!

As much as we would all like it to be that simple, there is a little more to it. The reason is that retirement plans (and the associated tax benefits) are meant for, well, retirement. Because of that, there are some detailed rules on what constitutes a “distributable event.” The limitations that apply to a given plan are spelled out in the plan document.

So, what are some factors to consider? Here are several:

- Is the participant requesting the distribution still employed or not? There are generally fewer restrictions for a former employee than for a current one.

- How old is the participant? Age 59 ½ is a “magic number” of sorts in terms of a participant being able to access his or her account as well as avoidance of an early withdrawal penalty.

- What types of contributions have been made to the plan for the participant? There are more restrictions on accessing 401(k) deferrals than there are for profit sharing contributions. Pre-tax deferrals are subject to individual income tax at the time of withdrawal, while Roth deferrals may be eligible for tax-free distribution.

- What does the plan document permit? Regardless of an individual participant’s situation, the plan document must specifically permit the payment in order for it to be made.

Loans

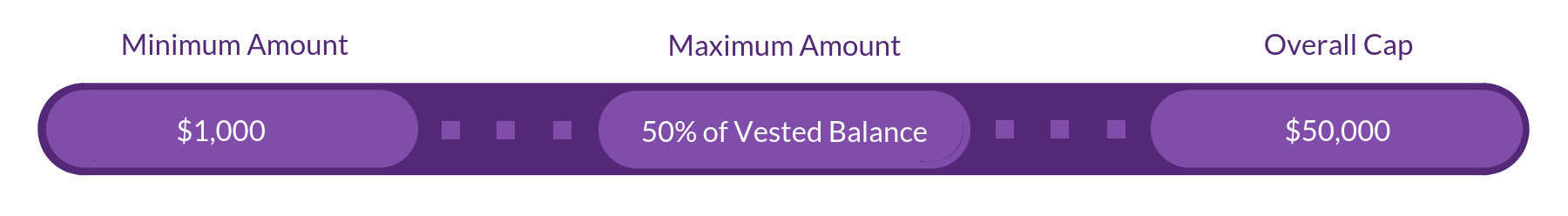

Many plans allow participants to take loans against their account balances. Typically, the minimum loan amount is $1,000, and the maximum is 50% of the participant’s vested account balance (subject to an overall loan cap of $50,000). Additional limitations apply if the participant had an outstanding loan at any point during the preceding year.

General purpose 401(k) loans must be repaid evenly over no more than five (5) years, while loans that are used for the participant to purchase a primary residence can often be amortized over much longer periods (sometimes as long as the first mortgage on the home). Regardless of the repayment period, most plans require that payments be made via after-tax payroll deduction to ensure that payments are made timely.

As long as loans are within the applicable limits and are fully repaid according to the amortization schedule, participants are not taxed on the loan amount. However, failure to properly repay a loan can result in the outstanding balance being treated as a distribution, subject to income tax and maybe an early withdrawal penalty.

Hardship Withdrawals

A participant who experiences an “immediate and heavy financial need” may be able to access his or her account to address the financial hardship. There are two general standards that can be used to determine whether a particular situation is sufficient to qualify for a hardship distribution. The so-called “facts and circumstances” standard is much broader but also requires someone, usually the plan sponsor, to analyze a participant’s situation and make a determination. Because of the subjectivity, most plans opt for the “safe harbor” standard, which spells out the criteria more objectively. There are still some subjective elements, but the “safe harbor” standard generally facilitates much more consistent adjudication of hardship withdrawal requests.

Amounts withdrawn due to hardship cannot be rolled over into an IRA or another plan, and they are subject to income tax in the year of distribution. The 10% early withdrawal penalty may also apply.

In-Service Distributions

Some plans allow participants to take in-service distributions while still employed, even without a financial hardship, once they reach a certain age or have been in the plan for a certain number of years. The law applies different age restrictions to different contribution sources. For example, 401(k) deferrals, safe harbor company contributions (match or nonelective), and certain “pension” accounts (those originating from a money purchase or defined benefit plan) are not available for in-service distribution until age 59 ½ (there’s that magic number again). Regular matching and profit sharing contributions as well as 401(k) rollover accounts are available at any age. Keep in mind that these are outside parameters, and the plan document will specify how these limitations apply to each individual plan.

The most common provision we see is to permit in-service distributions at age 59 ½, because all accounts are available at that age. That is also the point at which the 10% early withdrawal penalty no longer applies. Either way, in-service distributions are subject to individual income tax in the year received.

Required Minimum Distributions

Another important age is the point at which a participant is required to start taking minimum distributions. For those born on or before July 1, 1949, that age is 70 ½ (we’re not sure why Congress was so fascinated with half years, but that is a different conversation). Participants born after July 1, 1949 must begin taking those distributions at age 72.

Although the general rule is that a participant must begin taking required minimum distribution from the plan each year on attainment of age 70 ½ or 72, as applicable, there is an exception for active participants. Those who are not company owners (or who own less than 5% of the company) and are still employed by the plan sponsor can delay taking RMDs until they terminate employment.

The amount of each year’s is determined by dividing the participant’s account balance at the end of the previous calendar year by his or her remaining life expectancy (based on IRS mortality tables). The RMD must be paid out no later than December 31st each year (although the initial RMD can be as late as April 1st of the year following attainment of the RMD age requirement), and those distributions are subject to income tax in the calendar year of payment. If an RMD is not paid on time, the participant is subject to an excise tax equal to 50% of the RMD amount.

QDROs (Qualified Domestic Relations Orders)

A Qualified Domestic Relation Order is not a type of distribution, but it often leads to one. A QDRO is a court order, usually as part of a divorce proceeding, that awards a portion of a participant’s retirement plan account to a so-called “alternate payee” who is usually the former spouse. Most plans specify that an alternate payee can withdraw his or her account right away, even if the participant is not entitled to take a distribution of any remaining portion of his or her account. The alternate payee is subject to income tax on the withdrawal (unless it is rolled over to an IRA or another plan), but the 10% early withdrawal penalty does not apply.

Corrective Distributions

There are a number of limits and numerical tests that apply to plan contributions. From time-to-time, a participant may exceed those limits, or a plan may fall outside the parameters of those tests. In most of those situations, the fix is to distribute the amounts in question to the affected participants. These are not voluntary payments, so the plan is required to make them.

Corrective distributions are subject to income tax in the year of payment; however, they are not subject to the 10% early withdrawal penalty, and they are not eligible to be rolled over to an IRA or another plan.

Employment Terminations

Termination of employment with the plan sponsor is a distributable event, so that generally makes these types of requests the most straight-forward. Most plans are written to permit a former employee to take a distribution of his or her vested account balance immediately on termination of employment. However, that is not a foregone conclusion. Some plans make participants wait until the end of the quarter of termination, or even the end of the year, before taking a distribution.

In situations where a plan sponsor waits to deposit the company match or profit sharing contribution until the end of the year, a participant taking an immediate distribution may become entitled to an additional distribution once the contribution is deposited. If there is more than 180 days between the two, the participant must complete a whole new set of distribution request forms.

Termination distributions are subject to income tax and the 10% early withdrawal penalty if the participant is under age 59 ½. The participant can defer taxation by rolling over to an IRA or another plan.

Plan Terminations

When a plan sponsor chooses to formally terminate its plan altogether, each participant has a distribution event. Plan termination distributions work very similarly to employment termination distributions with one important distinction…a plan termination triggers immediate vesting for all participant accounts regardless of how long they have been employed. Other than that, the tax ramifications are the same, and participants can rollover to an IRA or another company-sponsored plan.

Mandatory Cash-Outs

Although former employees are generally permitted to keep their accounts in a company-sponsored plan as long as they want (at least until they must begin RMDs), there is an exception for those with small balances. Plans can be written to force terminated participants with small vested account balances to take their money out of the plan.

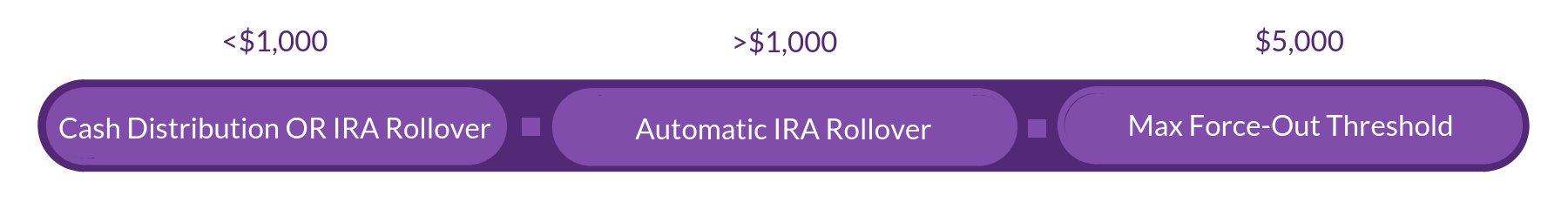

The maximum force-out threshold permitted is $5,000, but a plan can set a lower limit or even forego mandatory cash-outs altogether. If an account subject to force-out has a balance exceeding $1,000, the force-out is accomplished via automatic rollover to an IRA established on the participant’s behalf. If below $1,000, the plan document will specify whether the payment is made via cash distribution or automatic IRA rollover.

Mandatory cash-outs are subject to income tax, the 10% early withdrawal penalty (if under age 59 ½), and they are eligible for rollover to an IRA or another plan.

Disability

If a participant becomes disabled as defined by the plan, he or she is not subject to the 10% early withdrawal penalty on any distributions he or she is entitled to take.

For most types of distributions, the IRS requires that 20% of the distribution amount be withheld and remitted as payment of federal income taxes. Some states also have mandatory withholding. Service providers must follow these parameters and do not have the ability to waive or reduce the withholding.

There are several exceptions. The easiest one is for rollovers. In other words, if a participant elects to rollover his or her distribution to an IRA or another company-sponsored plan, the federal and state withholding requirements do not apply.

However, there are some types of distributions that are not eligible for rollover. These include RMDs, hardship distributions and corrective distributions. The default federal tax withholding for RMDs and hardships is 10%, but a participant can choose to increase, decrease or waive it. Corrective distributions are generally not subject to any type of federal withholding. Note that these exceptions apply only to the withholding at the time of distribution and not to the overall tax liability in general, which is determined when the participant prepares his or her tax return at the end of the year.